The Impact and Legacy of Futurism in Art and Design

In the tumultuous early 20th century, marked by a whirlwind of new inventions and a shift from agrarian to urban...

The Art Nouveau movement, which flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was characterized by its ornamental and organic designs. Here are some of the leading and important figures associated with the movement.

Art Nouveau, a captivating movement that flourished at the turn of the 20th century, is celebrated for its intricate designs, flowing lines, and harmonious connections between form and function. This aesthetic revolution, sweeping through Europe and beyond, birthed an era where art seamlessly blended with everyday life. In this post, we’ll delve into the lives and works of Art Nouveau artists who played pivotal roles in shaping this unique style. These visionaries transcended traditional boundaries, integrating natural motifs and sinuous forms into their creations. Their legacy, imbued with an unmistakable sense of beauty and innovation, continues to inspire and captivate art enthusiasts around the world.

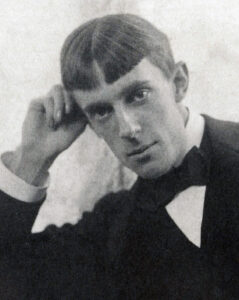

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley, born on August 21, 1872, in Brighton, England, emerged as a prominent English illustrator and author whose work played a pivotal role in the Aesthetic and Art Nouveau movements of the late 19th century. From an early age, Beardsley displayed a remarkable talent for drawing, leading him to attend various art schools, including the Westminster School of Art.

Beardsley gained widespread recognition at the age of 20 for his illustrations in Sir Thomas Malory’s “Le Morte d’Arthur“. Soon after, he became closely associated with the renowned playwright and poet Oscar Wilde. Notably, Beardsley illustrated Wilde’s play “Salomé“, creating a series of drawings that were not only artistically significant but also provocative and controversial in their content.

His artistic style was marked by bold lines, intricate patterns, and highly stylized, elongated figures. Beardsley’s drawings often incorporated elements of the grotesque and the erotic, challenging the societal norms prevalent in the Victorian era. His contributions to the literary and artistic magazine “The Yellow Book” further solidified his reputation for avant-garde and controversial content.

Beyond his collaboration with Wilde, Beardsley illustrated various literary works, including Alexander Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock” and Aristophanes’ “Lysistrata”. His drawings, often explicit and provocative, sparked controversy in the Victorian era, contributing to the artist’s notoriety.

Tragically, Aubrey Beardsley’s promising career was cut short by his untimely death at the age of 25, succumbing to tuberculosis in 1898. Despite the brevity of his life, his impact on the Art Nouveau movement and illustration was profound. His work continues to be celebrated for its originality and boldness, inspiring subsequent generations of artists and designers. His unique style characterized by intricate details and a sense of decadence continuing to captivate and inspire artists in the contemporary art world.

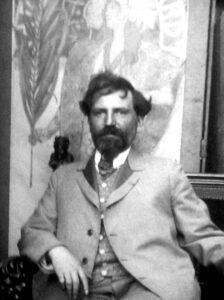

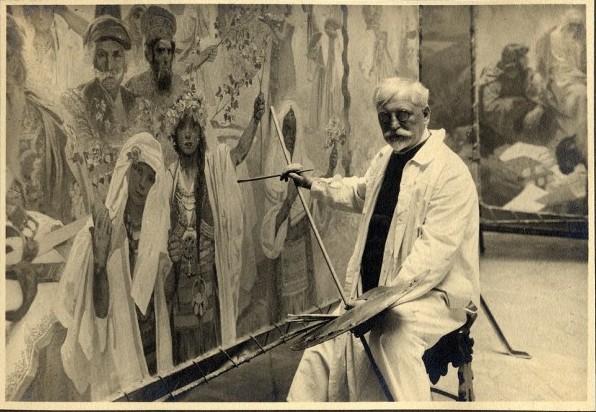

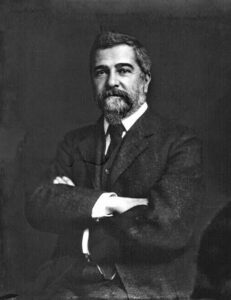

Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939) was a Czech artist and one of the most prominent figures associated with the Art Nouveau movement. His distinctive style, characterized by elaborate and decorative designs, made a significant impact on the aesthetics of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born on July 24, 1860, in Ivancice, Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic), Mucha initially studied singing and later moved to Vienna to pursue formal art training. He faced financial challenges, working odd jobs to support his education, and eventually moved to Paris in 1887.

Mucha’s breakthrough came when he was commissioned to create a poster for the renowned actress Sarah Bernhardt’s play “Gismonda” in 1894. The poster, characterized by its elegant, elongated female figure and intricate decorative elements, became an instant sensation. This marked the beginning of Mucha’s association with the Art Nouveau style.

Mucha’s Art Nouveau style was characterized by sinuous lines, floral motifs, and ornate details. His works often featured graceful women with flowing hair, surrounded by lush, natural forms. Mucha’s aesthetic was influenced by the organic shapes found in nature, and he sought to infuse beauty into everyday life.

The “Mucha Style” became synonymous with the decorative arts of the time. Mucha’s artistic output included not only posters but also illustrations, advertisements, postcards, and designs for jewelry, carpets, and wallpaper. His distinctive style extended to the interiors of theaters, particularly in the creation of decorative panels.

Later in his career, Mucha shifted his focus to more serious and monumental works. One of his notable projects was the “Slav Epic“, a series of 20 large-scale paintings depicting the history of the Slavic people. He conceived this project as a way to contribute to the cultural identity of his homeland.

Mucha was not only an artist but also engaged in civic and political activities. He was a strong advocate for Czechoslovak independence, and after the country gained independence in 1918, Mucha became involved in diplomatic and educational initiatives.

Alphonse Mucha spent his later years in the United States, where he continued his artistic endeavors and lectured on art. He passed away on July 14, 1939, in Prague. Mucha’s legacy endures through his contributions to the Art Nouveau movement, and his work continues to be celebrated for its decorative beauty and influence on subsequent generations of artists and designers. The Mucha Museum in Prague stands as a tribute to his life and work.

The French architect and designer, played a key role in the Art Nouveau movement with his distinctive contributions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Lyon in 1867, Guimard studied at the School of Decorative Arts in Paris. His work is particularly renowned for the iconic entrances he designed for the Paris Métro stations.

Guimard’s métro entrances, characterized by their sinuous, organic lines and intricate ironwork, exemplified the Art Nouveau aesthetic. The designs were not merely functional but served as artistic statements, blending seamlessly with the urban landscape. These entrances, often referred to as “Guimard Entrances“, became emblematic of the Paris Métro system.

Beyond his contributions to public transportation architecture, Guimard extended his artistic influence to various other projects. He designed furniture, interiors, and private residences, showcasing his commitment to the Art Nouveau principles of integrating art into everyday life. Guimard’s style was marked by its fluid, natural forms, drawing inspiration from nature and rejecting the rigid constraints of more traditional architectural styles.

Despite the initial controversy and resistance to his avant-garde designs, Guimard’s work had a lasting impact on the evolution of architectural and design aesthetics. His legacy endures, and the surviving examples of his métro entrances, along with other architectural contributions, stand as testaments to his significant influence on the Art Nouveau movement in France and beyond. Hector Guimard passed away in 1942, leaving behind a rich and enduring artistic legacy.

Louis Comfort Tiffany, an American artist and designer, made significant contributions to the Art Nouveau movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in New York City in 1848, Tiffany was the son of the renowned jeweler Charles Lewis Tiffany, the founder of Tiffany & Co. Despite being born into a family associated with luxury jewelry, Louis Comfort Tiffany carved his niche in the world of decorative arts.

Tiffany is most celebrated for his work in stained glass. His creations, including luminous stained glass windows, lamps, and other decorative objects, were characterized by vibrant colors and intricate designs. One of his most iconic designs is the Tiffany Lamp, featuring stained glass shades with nature-inspired motifs such as flowers, dragonflies, and geometric patterns.

In addition to stained glass, Tiffany extended his artistic talents to various mediums, including ceramics, jewelry, and mosaics. He embraced the Art Nouveau emphasis on organic forms and elaborate ornamentation, often incorporating natural motifs into his designs. Tiffany’s work reflected a departure from the more rigid Victorian aesthetic, offering a fresh and innovative approach to decorative arts.

Tiffany’s artistic vision extended beyond individual pieces; he played a pivotal role in the design reform movement and was a key figure in the American Arts and Crafts movement. His commitment to craftsmanship and attention to detail contributed to the elevation of decorative arts to the status of fine art.

The renowned Tiffany Studios, founded in 1902, became a hub for innovative design and craftsmanship. The studio produced a wide range of objects, from leaded glass windows to decorative vases, contributing to the widespread popularity of the Art Nouveau style in the United States.

Tiffany passed away in 1933, yet again his influence on the Art Nouveau movement left an indelible mark on American decorative arts. His commitment to craftsmanship, use of vibrant colors, and incorporation of natural elements into design continue to be celebrated.

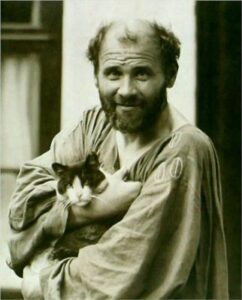

Gustav Klimt, an Austrian symbolist painter, was a prominent figure in the Vienna Secession Movement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Baumgarten, Austria, in 1862, Klimt showed early artistic talent and became a leading member of the Vienna art scene. His distinctive style and innovative approach played a crucial role in shaping the Art Nouveau movement.

Klimt’s paintings are known for their opulent and decorative qualities, often adorned with gold leaf. His work is characterized by symbolism, allegorical themes, and a focus on the human form, particularly the female figure. One of his most famous paintings, “The Kiss”, exemplifies his use of gilded surfaces, intricate patterns, and symbolic imagery.

As a founding member of the Vienna Secession in 1897, Klimt sought to break away from traditional artistic conventions. The Secessionists aimed to create a platform for avant-garde artists and promote a new, modern artistic language. Klimt served as the movement’s first president and contributed to the design of the Secession Building in Vienna, a testament to his commitment to the integration of art and architecture.

Klimt’s exploration of the female form was marked by sensuality and symbolism, often incorporating elements of mythology and allegory. His paintings, such as “The Tree of Life” and “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” showcase his intricate use of symbolism and decorative patterns, reflecting the prevailing themes of the Art Nouveau movement.

Beyond his canvas, Klimt was involved in various aspects of the decorative arts. He collaborated with other artists and designers, creating murals, friezes, and even designing his own studio. His work, often considered controversial at the time, garnered both praise and criticism, but it undeniably left a lasting impact on the trajectory of modern art.

Klimt passed away in 1918, but his innovative use of symbolism, decorative elements, and commitment to pushing artistic boundaries continue to influence and inspire artists to this day.

Émile Gallé, a French glass artist and furniture designer, emerged as a prominent figure in the Art Nouveau movement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Nancy, France, in 1846, Gallé came from a family with a rich tradition in ceramics and glassmaking. He played a pivotal role in elevating glasswork to the status of fine art.

Gallé’s artistic vision was deeply influenced by nature, and he was particularly known for his exquisite glassware adorned with intricate floral and natural motifs. He mastered the art of cameo glass, a technique involving layering different colored glass and then etching or carving to create intricate designs. His creations often featured delicate flowers, plants, and insects, showcasing a harmonious blend of craftsmanship and artistic expression.

As a founding member of the École de Nancy, a group of artists and designers dedicated to promoting Art Nouveau in the region, Gallé contributed significantly to the movement’s development. The École de Nancy sought to integrate art into daily life and to celebrate the beauty of nature through artistic expression. Gallé’s glasswork became synonymous with the ideals of Art Nouveau, characterized by flowing lines, organic forms, and a departure from the rigidity of academic styles.

In addition to his glasswork, Gallé extended his artistic talents to furniture design. He created unique pieces that reflected the same naturalistic and ornamental themes found in his glass creations. His furniture designs often incorporated innovative techniques and materials, further solidifying his reputation as a versatile and forward-thinking artist.

Gallé’s commitment to social and environmental causes was evident in his work. He believed in the ethical treatment of workers and the responsible use of natural resources. This commitment was reflected in his participation in social and political activities, advocating for reform and contributing to the broader cultural and intellectual landscape of his time.

Gallé passed away in 1904. His glasswork, furniture designs, and advocacy for ethical practices in the arts continue to influence contemporary artists and designers.

René Jules Lalique, a French glass designer and jeweler, played a pivotal role in the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Ay, France, in 1860, Lalique was drawn to the world of art and craftsmanship from a young age. His innovative and distinctive designs in glass and jewelry contributed significantly to the evolution of decorative arts.

His early works at international expositions won him worldwide acclaim and a prestigious clientele. Always original, he studied ancient techniques and pioneered new ones to create works of art, first in jewellery and later in glass.

Lalique’s early career was marked by his success as a jewelry designer. His creations, often characterized by the innovative use of materials such as glass, horn, and ivory, reflected a departure from the prevailing styles of the time. Lalique’s jewelry designs were intricate and inspired by natural motifs, such as plants, insects, and mythological figures, showcasing his fascination with the organic forms found in nature.

In the transition from Art Nouveau to Art Deco, Lalique’s work evolved, and he became a leading figure in the Art Deco movement. His glasswork, particularly the production of exquisite perfume bottles and decorative glass objects, became synonymous with luxury and craftsmanship. Lalique’s use of opalescent glass and his mastery of the “lost-wax” casting technique contributed to the uniqueness of his pieces.

“René Lalique had the gift of sending a frisson of beauty over the world.” – Henri Clouzot

One of Lalique’s notable achievements was his collaboration with renowned perfumer François Coty, for whom he designed a series of iconic perfume bottles. These bottles, adorned with intricate patterns and sculptural elements, not only contained fragrances but also served as objets d’art, reflecting Lalique’s belief in the fusion of beauty and functionality.

Lalique’s artistic vision extended beyond jewelry and glass to other mediums, including decorative arts and interior design. He created stunning glass panels, lighting fixtures, and even designed the interiors of luxury ocean liners, demonstrating his versatility as a designer.

René Lalique’s impact on jewelry design, glassmaking, and the broader field of decorative arts has left an indelible mark. Lalique passed away in 1945, but his eponymous brand, Lalique, continues to thrive, preserving and celebrating his artistic heritage. The Lalique Museum in Wingen-sur-Moder, France, stands as a testament to his influential contributions to the world of design and craftsmanship.

Victor Horta, a Belgian architect, stands as a pivotal figure in the Art Nouveau movement, contributing significantly to the evolution of architectural design during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Ghent, Belgium, in 1861, Horta’s innovative approach to architecture and emphasis on organic forms made him a central figure in the development of the Art Nouveau style.

Horta’s early career included studying architecture at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, where he honed his skills and absorbed influences from various artistic disciplines. His breakthrough came when he designed the Hôtel Tassel in Brussels in 1893, considered one of the first true Art Nouveau buildings. The Hôtel Tassel showcased Horta’s departure from traditional architectural norms, incorporating flowing lines, dynamic curves, and ornate details.

One of Horta’s defining features was his mastery of ironwork. He skillfully integrated wrought iron into his designs, creating intricate and elegant structures that became emblematic of the Art Nouveau aesthetic. His innovative use of materials extended to other elements, such as stained glass, mosaic, and innovative spatial arrangements, contributing to the overall harmony of his designs.

As a founding member of the Brussels-based artistic collective known as Les XX (The Twenty), Horta played a crucial role in promoting Art Nouveau in Belgium. His subsequent architectural projects, including the Hôtel van Eetvelde and the Maison & Atelier Horta, further solidified his reputation as a trailblazer in modern design.

Horta’s influence extended beyond architecture; he was instrumental in the foundation of the Société Libre des Beaux-Arts, advocating for artistic freedom and experimentation. His commitment to the unity of the arts was evident in his designs, where he seamlessly integrated architecture, interior design, and decorative arts.

Despite facing financial challenges and personal setbacks, including a brief imprisonment during World War I, Horta’s contributions to architecture were recognized later in his life. In 1932, he was awarded the title of Baron for his impact on Belgian architecture.

Victor Horta passed away in 1947, leaving behind a lasting imprint on the architectural landscape and the broader Art Nouveau movement. His innovative designs, characterized by organic forms and a departure from traditional structures, continue to inspire architects and designers worldwide.

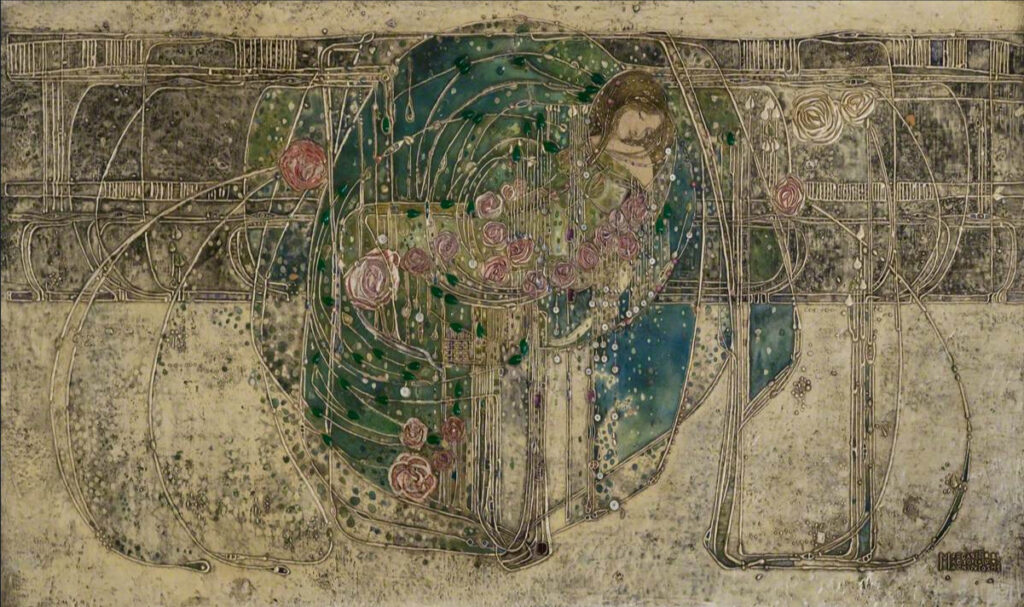

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, a Scottish artist and designer, made significant contributions to the Art Nouveau movement as a key member of the Glasgow School. Born in Tipton, England, in 1864, Margaret exhibited a remarkable artistic talent from a young age. She later moved to Glasgow, where she would become a central figure in the burgeoning art scene.

Margaret’s career is closely tied to her collaboration with her husband, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, another influential figure in the Glasgow School. Together, they produced innovative works that combined elements of Art Nouveau, Symbolism, and Japonism. Margaret’s artistic vision was characterized by intricate detailing, flowing lines, and a synthesis of form and function.

A notable aspect of Margaret’s work was her proficiency in various mediums, including textiles, metalwork, and watercolor. She played a crucial role in the creation of the “Glasgow Style“, an artistic movement that sought to unify the arts and crafts in pursuit of creating a total work of art. Margaret’s textile designs, often featuring elongated figures, plant motifs, and delicate patterns, exemplified the distinctive aesthetic of the Glasgow School.

The collaborative efforts of Margaret and Charles were evident in their interior design projects, where they created innovative and harmonious spaces. The Mackintoshes worked on projects such as the Willow Tea Rooms in Glasgow, where Margaret’s decorative panels and textiles complemented Charles’s architectural vision.

Margaret’s artistic output extended to book design and illustration, where she contributed to the distinctive appearance of publications associated with the Glasgow School. Her designs often featured symbolic and allegorical elements, reflecting the broader artistic and philosophical currents of the time.

Despite her significant contributions, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh’s work was sometimes overshadowed by her husband’s prominence. However, in recent years, there has been a renewed appreciation for her individual artistic achievements. Her influence on the Glasgow School and the Art Nouveau movement has gained recognition for its unique blend of symbolism, innovation, and dedication to the unity of art and craft.

Margaret passed away in 1933, but her multifaceted talent and collaborative efforts with Charles Rennie Mackintosh have left an indelible mark on the history of design, and her contributions continue to be celebrated as part of the broader legacy of the Glasgow School.

Josef Hoffmann, an Austrian architect and designer, played a crucial role in the Art Nouveau and later the Secessionist movements during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Brtnice, Moravia (now in the Czech Republic), in 1870, Hoffmann became a central figure in the development of modernist design and architecture.

Hoffmann’s early education took place at the Higher State Crafts School in Brno and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where he studied under Otto Wagner. Wagner’s influence and the prevailing Arts and Crafts movement inspired Hoffmann to embrace a holistic approach to design, integrating art and craft into everyday life.

In 1897, Hoffmann co-founded the Vienna Secession, a group of artists and designers seeking to break away from traditional artistic norms. The Secessionists aimed to promote new and innovative forms of artistic expression. Hoffmann’s designs for the group’s exhibitions, characterized by clean lines and geometric forms, demonstrated his commitment to modernism.

One of Hoffmann’s most significant collaborations was with the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops), an artisan cooperative he co-founded in 1903 with Koloman Moser and Fritz Waerndorfer. The Wiener Werkstätte aimed to create high-quality, handcrafted goods and encompassed a wide range of disciplines, including architecture, furniture, textiles, and graphic design.

Hoffmann’s architectural work exemplified the principles of the Vienna Secession. His designs, including the Stoclet Palace in Brussels and the Purkersdorf Sanatorium in Vienna, showcased a departure from historical ornamentation and a focus on geometric simplicity. The Stoclet Palace, in particular, is considered a masterpiece of Art Nouveau architecture.

As a designer, Hoffmann’s creations ranged from furniture and textiles to metalwork and ceramics. His furniture designs were characterized by clean lines, functional forms, and an emphasis on craftsmanship. Hoffmann’s commitment to creating a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, influenced his designs for interiors and everyday objects.

Hoffmann’s impact extended beyond Austria; he taught at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in Vienna and influenced a new generation of designers, including the likes of Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka.

Josef Hoffmann’s legacy is intertwined with the progression of modernist design and architecture. His contributions to the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte, along with his innovative approach to design, continue to be celebrated. Hoffmann passed away in 1956, but his influence endures as a significant force in the evolution of 20th-century design and architecture.

In the tumultuous early 20th century, marked by a whirlwind of new inventions and a shift from agrarian to urban...

As the twentieth century unfolded, emerging artists sought inspiration beyond the intricate designs of the Victorian era, Art Nouveau, and...

The Art Nouveau movement, which flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was characterized by its ornamental and...

As the 19th century unfolded, the city of Paris became a hotbed of optimism and creativity, fueled by a confluence...

In the mid to late 19th century, the technological change was a big driving force, just like today. The new...

While these developments were happening, the deskilling of the craftsman and manufacturing of mass-produced items, expansion of factories and even...

Before industrialization, things were made in small numbers, carrying the emotions and fingerprints of its creator as a result of...

In 1400s AD, after several years of focused experiments, Johannes Gutenberg made the system scalable and led the way for...

The history of graphic design begins with the cave paintings. The prehistoric humans were marking their daily lives or the...

Starting from a simple stone ax, throughout the history we created a man-made environment, to survive and control the world...