The Impact and Legacy of Futurism in Art and Design

In the tumultuous early 20th century, marked by a whirlwind of new inventions and a shift from agrarian to urban...

As the 19th century unfolded, the city of Paris became a hotbed of optimism and creativity, fueled by a confluence of factors: peace, prosperity, and an increase in leisure time. This era witnessed a surge in artistic expression, driven by the Industrial Revolution’s production of everyday goods and the evolution of printing technologies.

Jules Chéret, born into a financially modest yet artistically inclined family in Paris, embarked on a remarkable journey that would redefine the landscape of advertising and poster design. Hindered by limited resources, his formal education concluded early, leading him to a transformative three-year apprenticeship with a lithographer at the tender age of thirteen. Chéret’s latent interest in painting propelled him to the Ecole Nationale de Dessin, where he immersed himself in the techniques of various masters housed in Parisian museums.

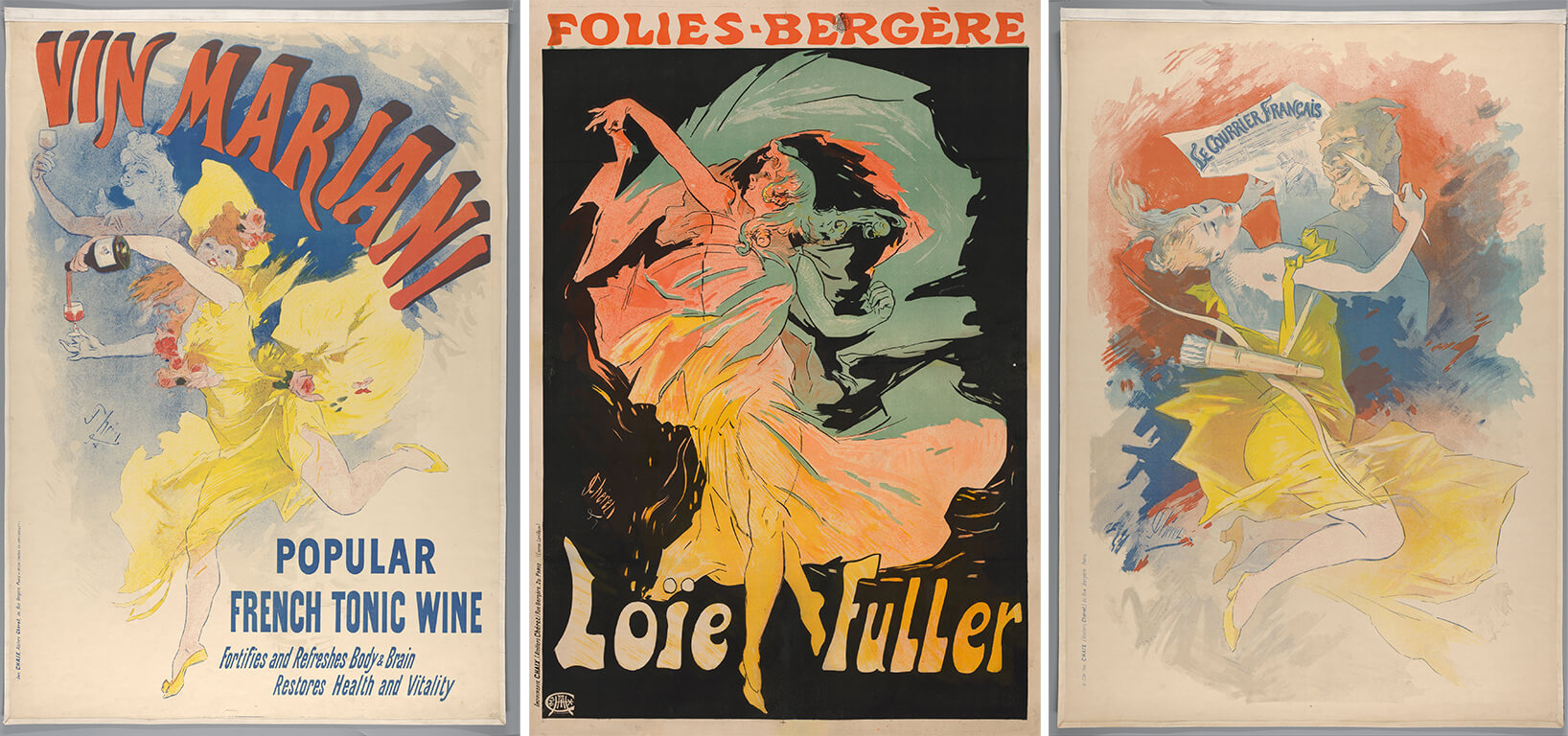

A sojourn to London from 1859 to 1866 provided Chéret with invaluable lithography training. Armed with these skills, he returned to France and unleashed his artistic prowess in crafting dazzling posters for renowned Parisian cabarets and theaters. The success of his advertisement business burgeoned, encompassing diverse consumer goods like liquors, perfumes, soaps, cosmetics, pharmaceutical products, and promotional materials for railway companies and manufacturing firms.

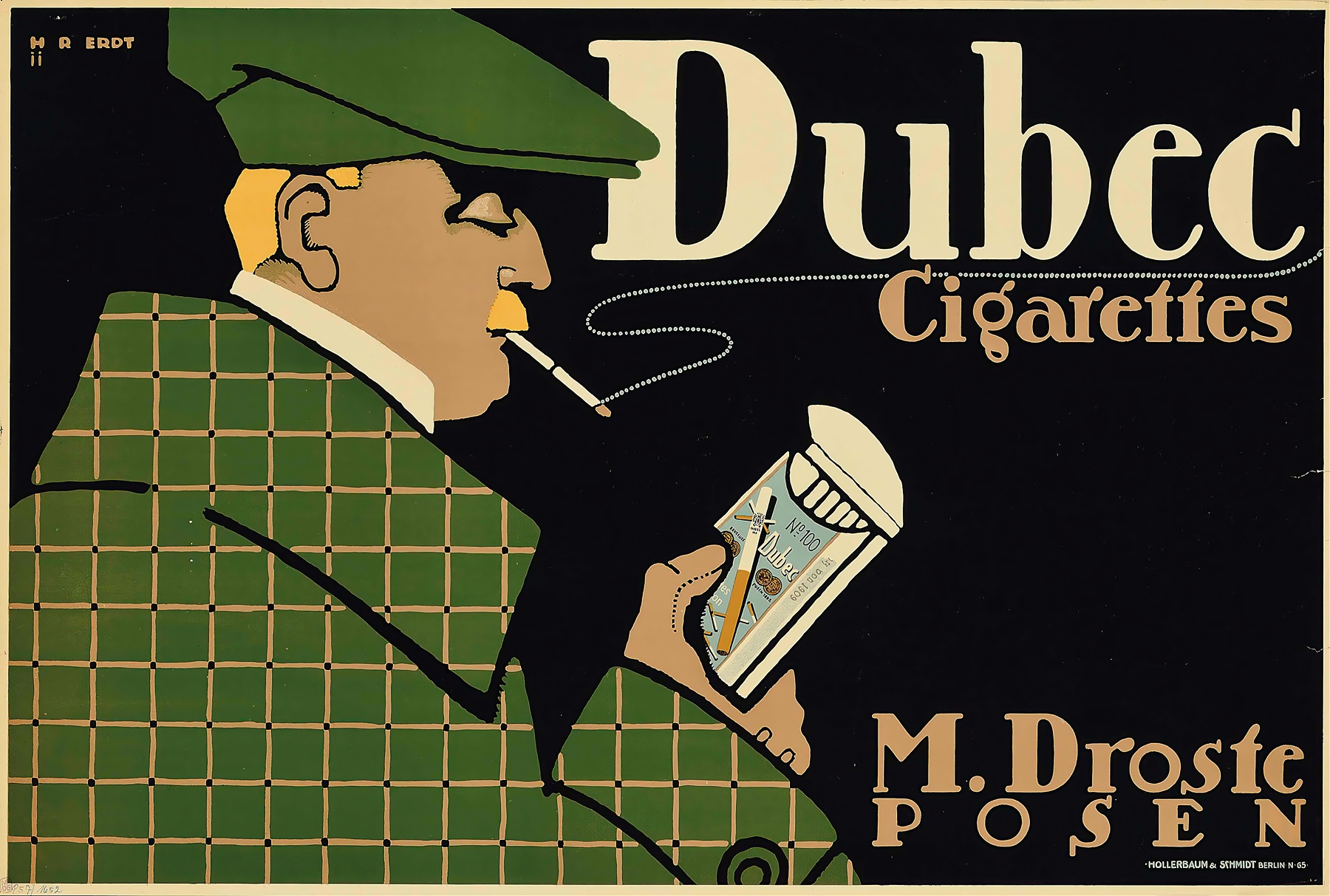

As the 19th century drew to a close, vibrant and expansive posters adorned the main streets of industrialized metropolises worldwide. These large, colorful creations became a familiar sight, capturing the attention of the general public and earning recognition from art connoisseurs. Galleries proudly exhibited these posters, and art critics, recognizing their aesthetic merit, appraised their compositions in esteemed art journals. The demand for these artistic gems soared among avid art collectors.

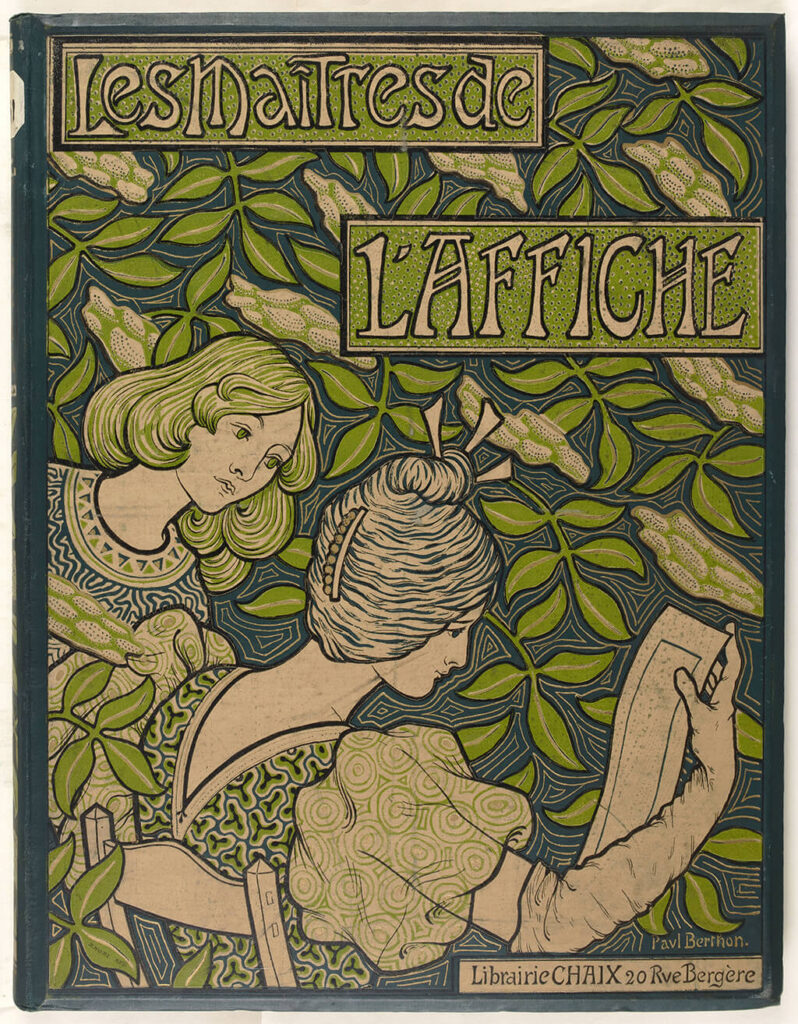

During the waning years of the Fin de siècle period, Jules Chéret’s Imprimerie Chaix played a pivotal role by publishing the most exquisite posters of the era. Over 90 European and American artists contributed to this collection, collectively known as “Les Maitres de l’Affiche” (Masters of the Poster). This period, referred to as “La Belle Époque” or the Golden Age, was characterized by its vivid colors, visual extravagance, daring designs, voluptuous styles, and an exaggerated emphasis on realistic details.

This era marked a pinnacle in the fusion of art and advertising, with posters evolving into celebrated works of art that transcended their initial commercial purpose. La Belle Époque not only encapsulated the spirit of the times but also left an enduring legacy in the annals of art history, highlighting a period where creativity and aesthetics flourished on the bustling streets of the industrialized world.

Chéret’s triumph paved the way for a new wave of poster designers and painters, including Charles Gesmar and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, with Georges de Feure among his students. Departing from conventional typographic solutions, Chéret introduced illustrations and a more painterly approach to his posters, radiating frivolity and joy. His groundbreaking portrayal of women, termed ‘Cherettes,’ marked a significant departure from traditional depictions, empowering Parisian women and leaving an indelible mark on the social fabric of the city.

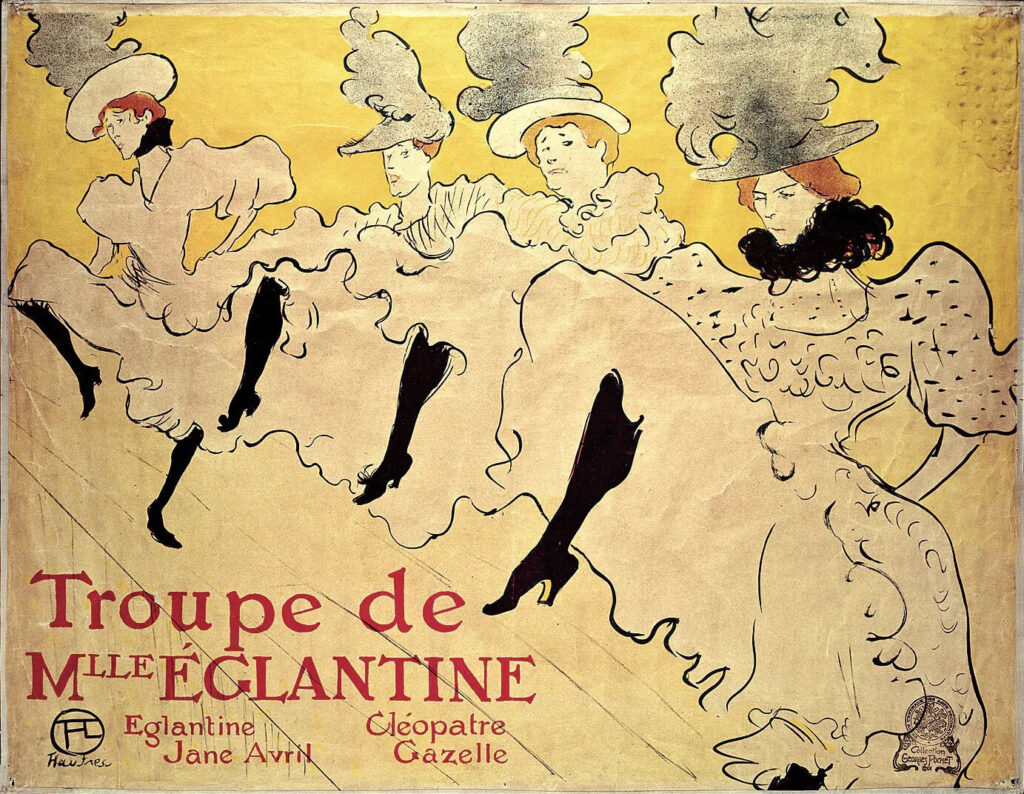

During the same era, the influence of Japanese woodblock prints, known as “ukiyo-e” left an indelible mark on Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. This genre, thriving in Japan from the 17th to the 19th centuries, featured woodblock prints and paintings depicting various subjects, including female beauties and theatrical scenes.

From the 1870s onward, the trend of Japonism gained prominence, impacting early Impressionist luminaries such as Degas, Manet, and Monet, as well as artists of the Art Nouveau movement like Toulouse-Lautrec. Adopting Jules Chéret’s approach of image-based posters, Toulouse-Lautrec navigated towards a flatter and simpler form, echoing the aesthetics of Japanese woodblock prints.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s integration of typography, while less refined than Chéret’s, embraced a looser approach, reminiscent of the Japanese woodblock style. The strategic use of large expanses of negative space and implied form further echoed the influence of ukiyo-e.

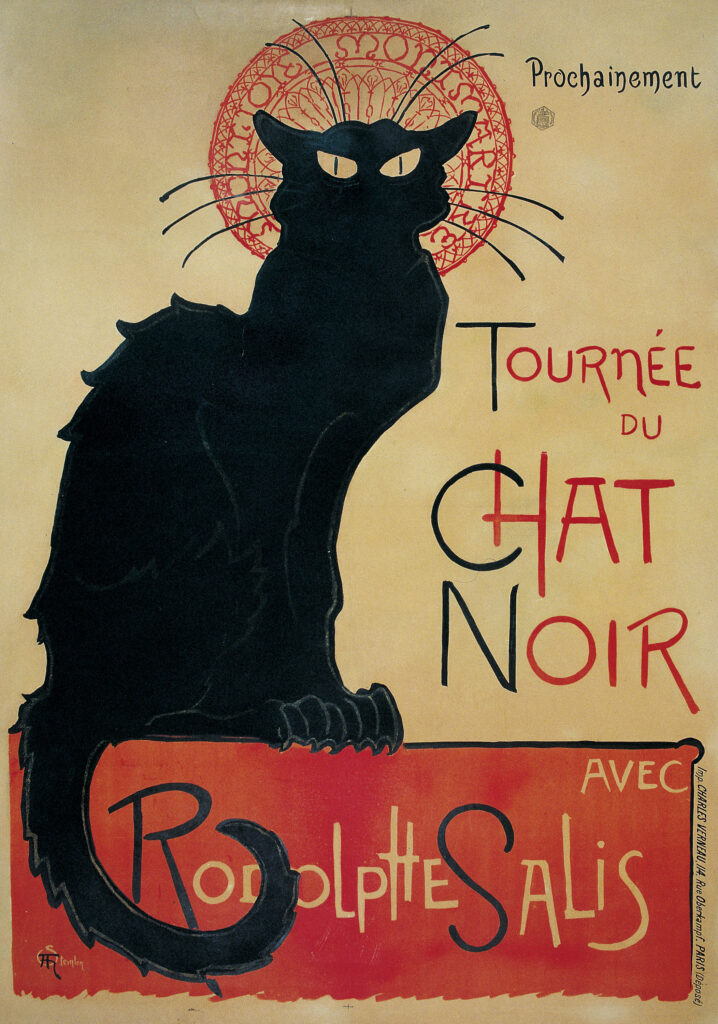

Artists like Theophile Alexandra Steinlein shared Toulouse-Lautrec’s enthusiasm for Japanese woodblock art and impressionism, as seen in Steinlein’s poster for Le Chat Noir.

The creative explosion of this period in Paris, fueled by the vibrant energy of the era, found expression in these posters. They reflected the dynamism and vitality of the time, ushering in a paradigm shift from the informational and static posters of the past to an era of energetic, image-driven design.

As the 19th century waned, the industrial age’s allure juxtaposed starkly against its societal repercussions. This era birthed technological innovations—automobiles, telephones, electric power, and towering skyscrapers—heralding an age of progress. Yet, this progress came at a cost: urban slums, environmental degradation, and exploitative labor practices, including child labor, marred the landscape of advancement.

Art Nouveau emerged as a response to these contradictions, offering a stylistic rebuke to industrialization’s excesses. Rooted in natural forms and the nostalgic idealization of a pre-industrial past, Art Nouveau sought to harmonize art, design, and living. It envisioned a world where beauty and functionality intertwined, drawing inspiration from natural motifs and medieval craftsmanship to counter the industrial era’s alienation.

The movement, blossoming in the 1890s, represented a synthesis of diverse artistic impulses. Artists delved into their national heritage while also drawing from Asian and Middle Eastern aesthetics, pioneering a global exchange of ideas. This era of artistic ferment saw the exploration of new materials and techniques, aiming for an integrated approach to design that encompassed everything from architecture to everyday objects.

Art Nouveau’s influence spanned the gamut of creative expression, encapsulating the late 19th century’s search for a design ethos that could embody both the beauty of the natural world and the spirit of modernity. As a dynamic confluence of cultural influences and innovative design, Art Nouveau mirrored the complexities of an age poised between tradition and the forward march of technology.

The term “Art Nouveau” made its debut in the 1880s within the pages of the Belgian review L’Art Moderne, characterizing the endeavors of “Les Vingt” a collective of 20 painters and sculptors committed to reform through art. This movement resonated with a broader artistic community spanning Europe and America, echoing the sentiments of leading nineteenth-century theorists such as French neo-Gothic architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and British art critic John Ruskin. These theorists advocated for the unity of all arts, challenging the traditional segregation between the fine arts of painting and sculpture and the often marginalized “decorative arts.”

The Art Nouveau style, characterized by its whimsical motifs drawn from the natural world, emerged between the 1880s and the outbreak of World War I. It exerted a profound influence on various artistic expressions, particularly in applied arts, graphic work, and illustration. The hallmark sinuous lines and “whiplash” curves found in Art Nouveau were, in part, inspired by botanical studies and depictions of underwater vegetation. The harmony embodied in the flowing lines of Art Nouveau can be interpreted as a deliberate attempt by its practitioners and admirers to liberate their art from the constraints of artistic tradition and conventional expectations.

Indeed, Art Nouveau was a concerted effort to forge an international style rooted in decorative elements. The movement was propelled by a vibrant and innovative generation of artists and designers who were determined to craft an artistic expression suited to the evolving landscape of the modern age. This extraordinary period witnessed the establishment of urban life as we recognize it today, marked by a coexistence of old customs, habits, and artistic styles alongside the emergence of novel concepts.

Art Nouveau sought to encapsulate the spirit of this dynamic era, blending a diverse array of contradictory images and ideas. The movement, with its emphasis on decorative motifs inspired by the natural world, aimed to break away from the constraints of traditional artistic styles. It was a response to the changing times, as industrialization and urbanization brought about a shift in societal structures and cultural norms.

Art Nouveau became a unifying force, transcending national boundaries to create a shared aesthetic language that resonated across various countries and cultures. Its legacy lies not only in decorative elements but also in its role as a reflection of the complex and multifaceted nature of the modern age. It captured the spirit of a generation that was eager to break free from artistic conventions, embracing the new and the experimental.

Art Nouveau’s legacy holds a significant place in art and design history as the first recognized “modern” style. It marked a groundbreaking departure from established artistic conventions, representing the initial instance where design was actively promoted through mass communication channels. Despite its lineage from the Arts & Crafts movement, which sought a return to traditional craftsmanship, Art Nouveau embraced a forward-looking perspective at the turn of the century.

Art Nouveau embodied a paradoxical blend of progressive ideals and a nod to historical craftsmanship, forging a distinct path as the inaugural “modern” style that would set the stage for subsequent artistic movements and design trends.

Beyond its role as a groundbreaking design movement, Art Nouveau delved into modern psychology and sexuality. It marked the first concerted effort to navigate the complexities of human emotions and sensuality within the realm of design. This distinctive approach garnered global popularity at the turn of the century, driven by the notion that everyday items could embody a range of emotions, from the sensual to the tragic.

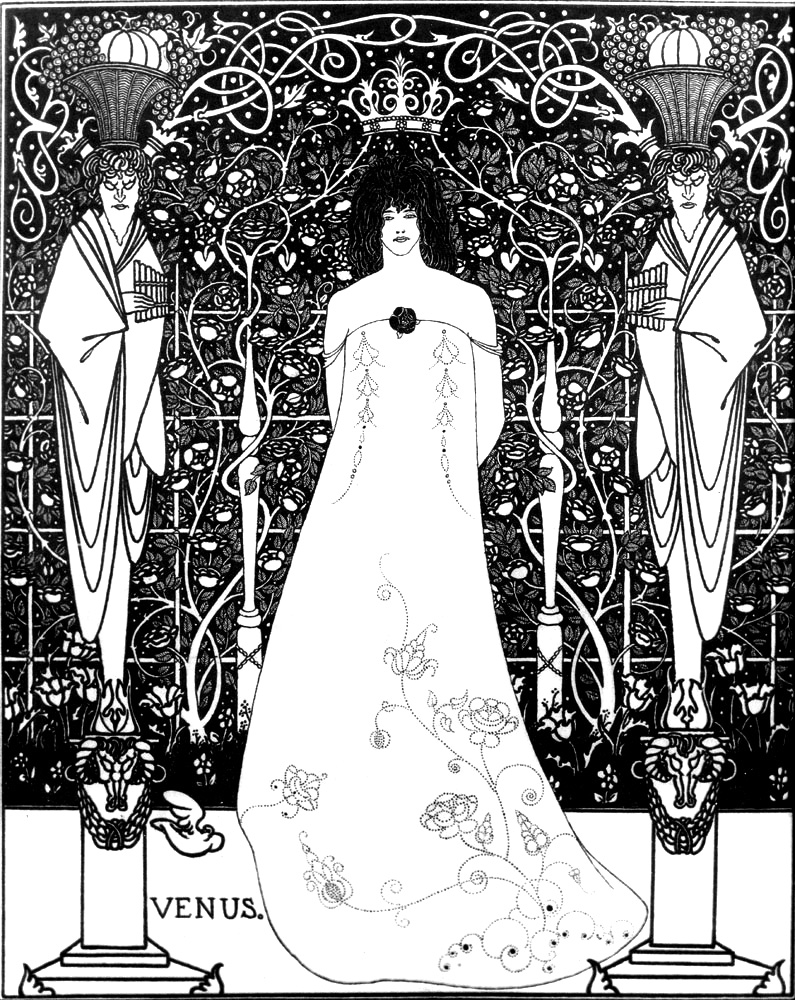

In the contemporary context, the infusion of emotion into design has waned, replaced by a prevailing love for technology and impersonal modes of communication in the twenty-first century. However, Art Nouveau stands as a testament to a bygone era where the whole spectrum of human emotions found expression through ordinary objects. Whether it was the immersive experiences of nature or Aubrey Beardsley’s provocative and erotic drawings, Art Nouveau encapsulated the multifaceted nature of human sentiment.

This emotional resonance extended across various everyday objects, transforming them into vessels of artistic expression. Candlesticks, chairs, and even the entrances to the Paris Metro adopted the distinctive and evocative aesthetics of Art Nouveau. Among the notable figures in this movement, Aubrey Beardsley emerged as its rebellious figure, often referred to as the “bad boy” of Art Nouveau. His illustrations in books and limited edition prints delved into the grotesque and the erotic, characterized by stark black-and-white compositions with high contrast. The fluid shapes evident in Beardsley’s work, and in Art Nouveau more broadly, drew clear inspiration from the organic forms of the natural world, reinforcing the movement’s commitment to a harmonious integration of art and nature.

The journey through 19th-century Parisian streets unveils a remarkable epoch of artistic evolution, from the vibrant posters of Chéret to the global impact of Art Nouveau. This period serves as a testament to the dynamic spirit of creativity and innovation that paved the way for the modern artistic landscape.

Art Nouveau, characterized by its intricate designs and organic motifs, met its decline in a manner similar to the lifecycle of a flower. Initially, it blossomed from the innovative efforts of a few, reaching a peak of popularity and influence. However, as its stylistic elements became widely adopted, the movement’s essence began to dilute. The proliferation of Art Nouveau in commercial merchandise and graphics, especially through posters and periodicals, extended its reach but also led to a compromise in design quality. Manufacturers prioritized profitability over artistic integrity, producing vast quantities of Art Nouveau items that often lacked the originality and high standards set by the movement’s pioneers.

This commercialization, coupled with the advent of World War I, which shifted societal and political priorities dramatically, contributed to Art Nouveau’s decline. The war’s emphasis on nationalism and the subsequent changes in public sentiment rendered the movement’s aesthetic joys and ideals seemingly irrelevant. As a result, Art Nouveau faded away, leaving behind a legacy that influenced future generations not through its specific stylistic choices but through its approach to materials, processes, and value.

The end of Art Nouveau marked the beginning for new design philosophies that diverged from its highly decorative and naturalistic tendencies. Twentieth-century designers, influenced by Art Nouveau’s innovative spirit, sought fresh approaches that emphasized functionality, simplicity, and modernity. This transition set the stage for movements like Art Deco, which embraced geometric forms, industrial materials, and a more streamlined aesthetic. Additionally, the Bauhaus movement emerged, advocating for the unification of art, craft, and technology, and promoting designs that were accessible to all. These movements, along with others such as Modernism, built upon Art Nouveau’s legacy of creativity and exploration but shifted towards designs that reflected the changing social, economic, and technological landscape of the 20th century.

The late 19th century was a crucible of creativity, where artists dared to challenge norms, embrace contradictions, and forge a path toward a new artistic dawn. The echoes of this transformative period continue to reverberate, reminding us that the intersection of art and society is a dynamic realm where innovation and expression intertwine to shape the course of cultural history.

In the tumultuous early 20th century, marked by a whirlwind of new inventions and a shift from agrarian to urban...

As the twentieth century unfolded, emerging artists sought inspiration beyond the intricate designs of the Victorian era, Art Nouveau, and...

The Art Nouveau movement, which flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was characterized by its ornamental and...

As the 19th century unfolded, the city of Paris became a hotbed of optimism and creativity, fueled by a confluence...

In the mid to late 19th century, the technological change was a big driving force, just like today. The new...

While these developments were happening, the deskilling of the craftsman and manufacturing of mass-produced items, expansion of factories and even...

Before industrialization, things were made in small numbers, carrying the emotions and fingerprints of its creator as a result of...

In 1400s AD, after several years of focused experiments, Johannes Gutenberg made the system scalable and led the way for...

The history of graphic design begins with the cave paintings. The prehistoric humans were marking their daily lives or the...

Starting from a simple stone ax, throughout the history we created a man-made environment, to survive and control the world...