The Impact and Legacy of Futurism in Art and Design

In the tumultuous early 20th century, marked by a whirlwind of new inventions and a shift from agrarian to urban...

In the tumultuous early 20th century, marked by a whirlwind of new inventions and a shift from agrarian to urban living, radical changes unfolded across political, social, cultural, and economic landscapes. Amidst the chaos, Futurists emerged, rejecting tradition and embracing the rapid transformations brought by scientific and technological advancements.

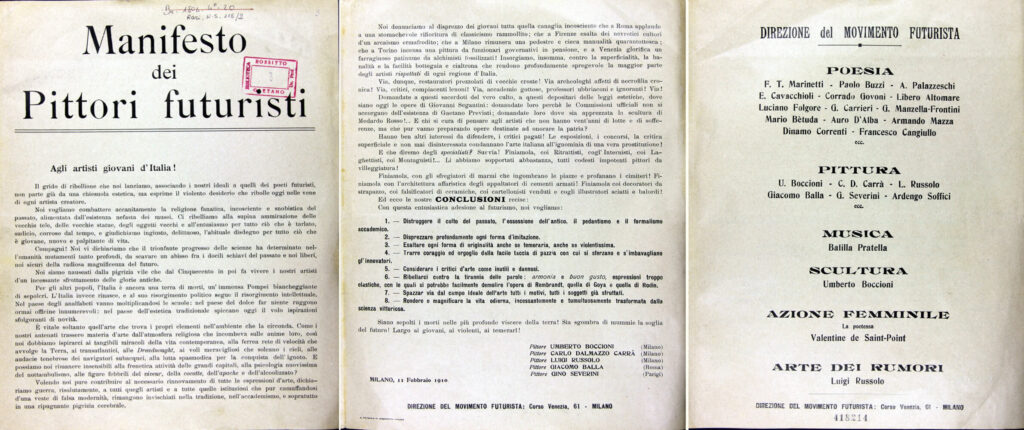

Enter the Futurists, a collective founded in 1909 in Italy by poet Filippo Marinetti. Dissatisfied with the pace of change, they sought to celebrate the components of the emerging industrial society—speed, machines, war, and revolution. Marinetti’s provocative “Manifesto of Futurism“, published in 1909, boldly rejected the past, championing change, originality, and industrialism. It declared war on museums, libraries, and what it perceived as utilitarian cowardice.

Visual artists within the movement sought a radical departure from conventional representation. Convinced that traditional art forms couldn’t capture the essence of the new reality, Futurists called for the destruction of outdated assumptions about vision and language. Marinetti envisioned a detachment from history, advocating for a new aesthetic centered on speed and energy, particularly celebrating aggressive war machines.

In 1910, prominent Futurists, including Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Carrà, signed the Manifesto of the Futurist Painters, rebelling against the worship of old art and advocating for the destruction of outdated beliefs. In the Manifesto, they wrote;

“We will fight with all our might the fanatical, senseless and snobbish religion of the past, a religion encouraged by the vicious existence of museums. We rebel against that spineless worshiping of old canvases, old statues and old bric-a-brac, against everything which is filthy and worm-ridden and corroded by time. We consider the habitual contempt for everything which is young, new and burning with life to be unjust and even criminal.”

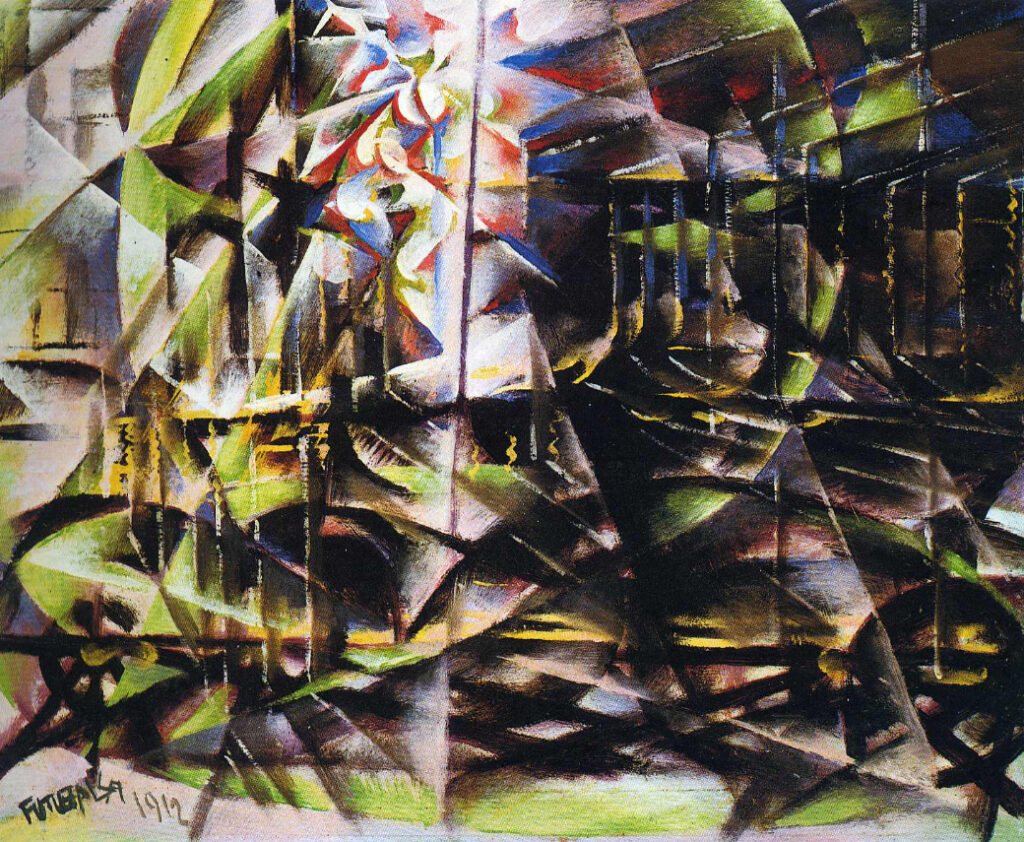

The movement’s graphic art was groundbreaking, introducing dynamism and speed in visual communication, abandoning traditional perspectives for the kinetic energy of machines and crowds.

Inspired by philosopher Henri Bergson, Futurist formalism conveyed kinetic energy, duration, and simultaneity. Their compositions disrupted forms and embraced “simultaneity,” opening up to the surroundings. The result was a polysensorial transcription of experience, exploring new avenues of experimentation.

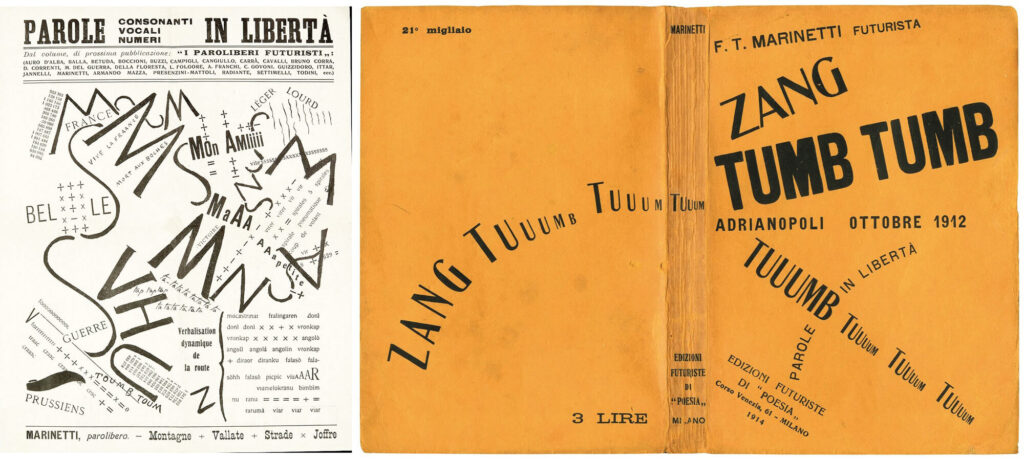

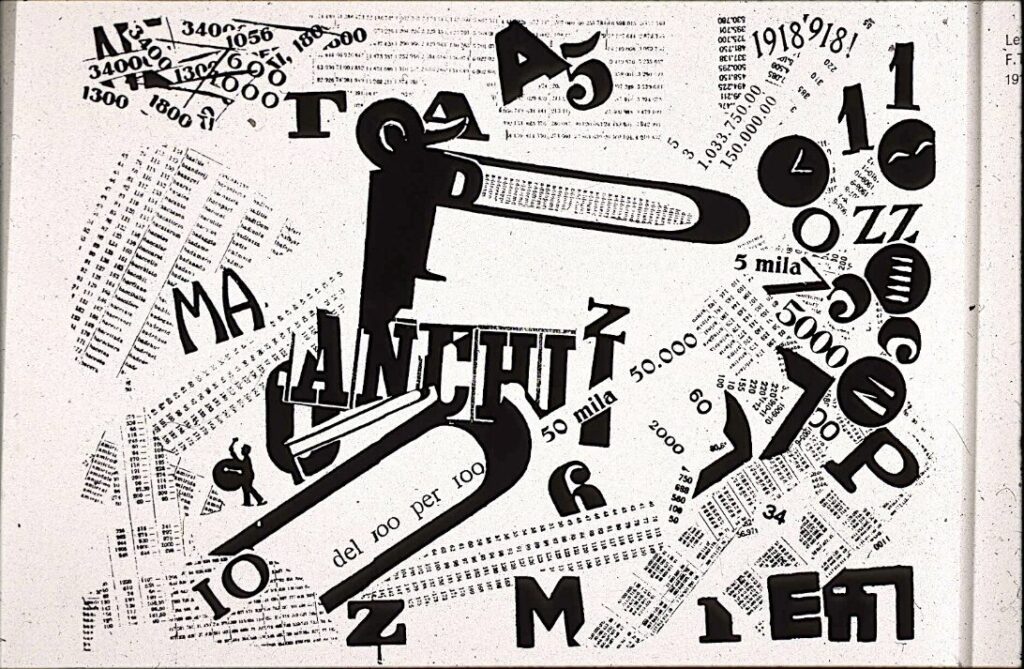

Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism also revolutionized typography, using ink colors and typefaces strategically to enhance expressive power. A new painterly typographic design, “parole in libertá” or “words in freedom” emerged, liberating poetry from grammar’s shackles.

Breaking away from Gutenberg’s horizontal and vertical structures, Futurist poets embraced non-linear, dynamic composition. They believed writing and typography could be concrete and expressive visual forms. This idea manifested in pattern poetry, where verses took the shape of objects or symbols, reinforcing intended auditory sounds.

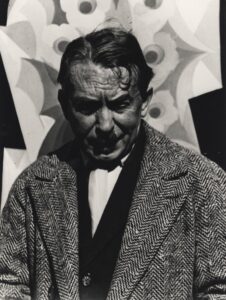

Filippo Tommaso Emilio Marinetti (1876–1944) was an Italian poet, writer, art theorist, and the founder of the Futurist movement. Born in Alexandria, Egypt, Marinetti played a key role in shaping the avant-garde cultural scene in the early 20th century. In 1909, he published the “Futurist Manifesto” in the French newspaper Le Figaro, outlining the principles of Futurism.

Marinetti’s Futurism was characterized by a celebration of modernity, technology, speed, and the rejection of traditional artistic and societal norms. He embraced the dynamism of the modern world and called for a break from the past, advocating for a new aesthetic that captured the energy and vitality of contemporary life.

Beyond his literary contributions, Marinetti was actively involved in various artistic endeavors, including visual arts, theater, and even the design of a new Futurist cuisine. He was a leading figure in the development of Futurist graphic design and experimented with innovative typographic layouts.

While initially supportive of Mussolini and the Fascist regime in Italy, Marinetti’s relationship with the government became strained over time. Despite his initial enthusiasm for war, Marinetti’s later years were marked by disillusionment and criticism of the direction taken by the Fascist regime.

Fortunato Depero, born in 1892 in Fondo, Italy, began his artistic journey with an apprenticeship as a marble worker in 1900. His early exposure to art and design skills laid the foundation for his future endeavors. In 1913, he encountered Futurism through the Futurist paper ‘Lacerba‘, sparking a deep interest in the movement’s art and design principles. Inspired by Marinetti’s Futurist ideas, Depero became a key figure in the Futurist movement, particularly in the realm of graphic design and modern advertising.

Although not among the leading members of the Futurist movement, Depero proved to be one of its most dedicated adherents. Born in Trentino at Alto Adige under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he initially trained as a traditional craftsman and attempted to enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, only to be rejected. Depero’s pivotal moment came in 1913 when he read Marinetti’s article on Futurism in Lacerba while in Florence. This inspired him to publish his collection of poetry, prose, and illustrations titled ‘Spezzature–Impressioni: Segni e ritmi‘ before moving to Rome, where he met Marinetti and other Futurists.

In 1915, Depero, along with Giacomo Balla, authored the manifesto “Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo” or “Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe“, advocating for the application of various media in art to create dynamic ‘plastic complexes‘. This period marked the beginning of Depero’s active involvement in the Futurist movement, leading to his solo exhibition in Trento in 1914, which was unfortunately cut short due to the outbreak of World War I. Undeterred, Depero volunteered for the front lines and actively participated in the war.

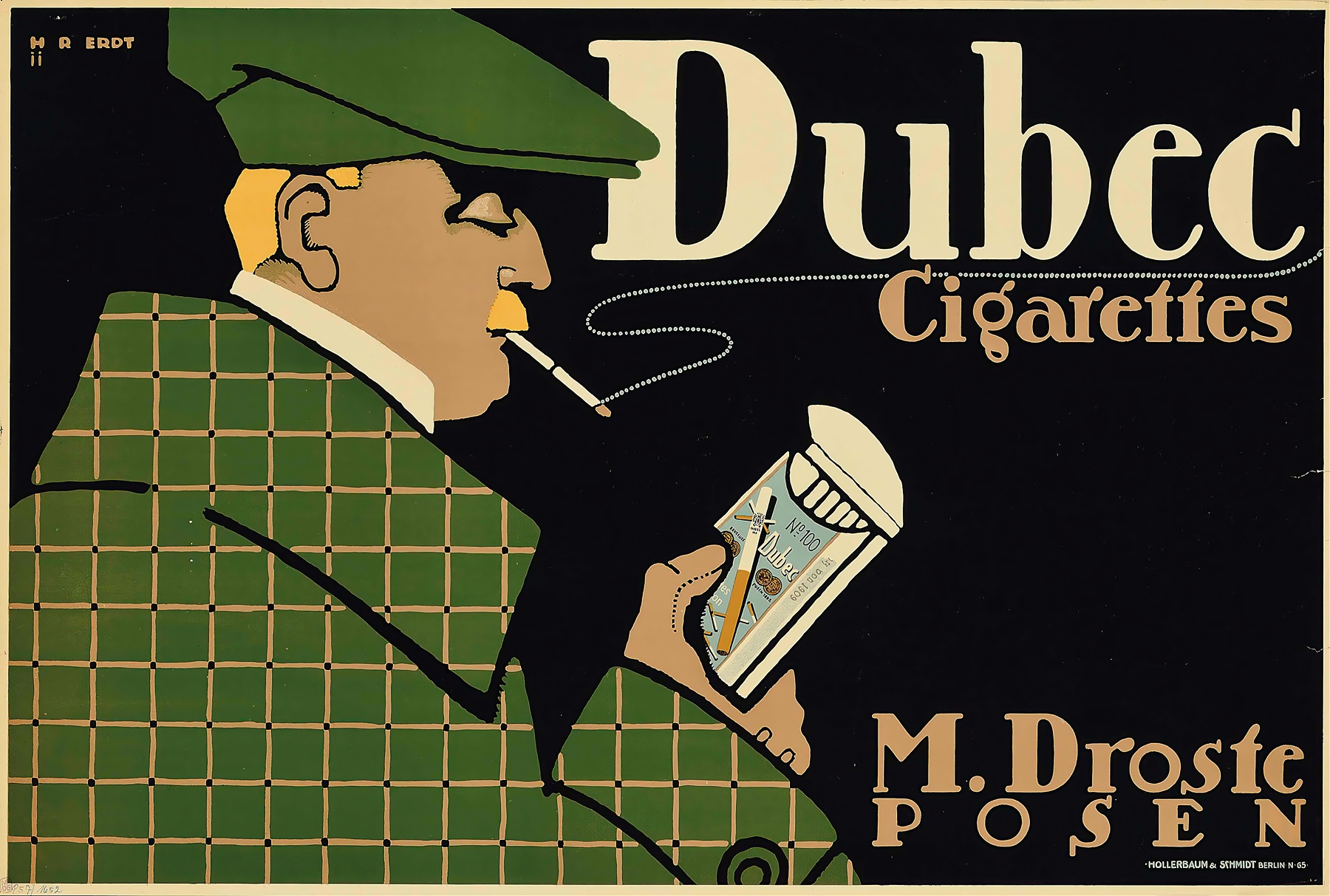

During the ‘second wave’ of Futurism, Depero played a crucial role in revitalizing typographically experimental texts. He embraced Marinetti’s ‘parole in libertà‘ poetry, combining it with bruitist barrages of noise to revolutionize typographic expression. Unlike some Futurists who favored eccentric streamlined lettering, Depero injected an exuberant, Mediterranean-influenced palette into his designs, introducing a playfully dynamic Futurist aesthetic into commercial and political advertising. His rejection of classical types in favor of innovative lettering styles symbolized the movement’s emphasis on speed and modernity.

Giacomo Balla (1871–1958) was a prominent Italian painter associated with the Futurist movement. Born in Turin, Italy, Balla received his artistic training at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Turin, where he honed his skills as a painter.

Balla became introduced to Futurism in the early 20th century and wholeheartedly embraced the movement’s core principles, which focused on capturing the dynamism, speed, and modernity of contemporary life through artistic expression. His collaboration with Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the founder of Futurism, was particularly noteworthy. Together with Fortunato Depero, Balla co-authored the “Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe” manifesto in 1915.

In terms of artistic style, Balla’s work was characterized by a fascination with movement and light. He often painted dynamic scenes of urban life, emphasizing the effects of light on surfaces and the motion of objects. One of his most famous works, “Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash” (1912), exemplifies his innovative approach by depicting the movement of a dog and its leash through a series of dynamic, abstract shapes. His curvilineal repetitive patterns represented the hectic pulse of modern life in its rhythmic throbbing of a mechanistic surrounding.

Balla, like other Futurists, explored the principles of simultaneity and dynamism in his art. His paintings sought to capture the essence of modern life, including the speed of technological advancements and the vibrant energy of the urban environment.

In addition to his contributions to painting, Balla co-authored the “Futurist Manifesto of Men’s Clothing” in 1914 with Umberto Boccioni. This manifesto advocated for radical changes in fashion to reflect the dynamism and progress of the modern era.

After World War I and the decline of the Futurist movement, Balla’s artistic style evolved, and he embraced a more traditional approach to art. Nevertheless, his impact on the history of modern art remains significant. Balla continued to paint and teach art until his death in 1958, leaving behind a legacy as one of the prominent figures of the Futurist movement.

Futurists despised classical harmony, viewing it as a relic of a culture fixated on the past. Typography became their canvas, energetic and illegible, collaging elements from different sources. The movement met its end in 1918, with many Futurists enlisting in World War I, aligning with their earlier reverence for war, violence, and the destruction of the old. By war’s end, only a few Futurists survived, marking the conclusion of a movement that reshaped the artistic and design landscape.

While it was predominantly an Italian marvel, similar artistic currents were evident in Russia, England, and other locations. The allure of Italian Futurism reached beyond its borders, captivating artists like Kazimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova, and David Burliuk in England and Russia. Italian Futurism’s bold spirit also permeated through and subtly influenced the development of artistic movements such as Art Deco, Constructivism, Surrealism, and Dada, while more significantly shaping the contours of Precisionism, Rayonism, and Vorticism.

In the tumultuous early 20th century, marked by a whirlwind of new inventions and a shift from agrarian to urban...

As the twentieth century unfolded, emerging artists sought inspiration beyond the intricate designs of the Victorian era, Art Nouveau, and...

The Art Nouveau movement, which flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was characterized by its ornamental and...

As the 19th century unfolded, the city of Paris became a hotbed of optimism and creativity, fueled by a confluence...

In the mid to late 19th century, the technological change was a big driving force, just like today. The new...

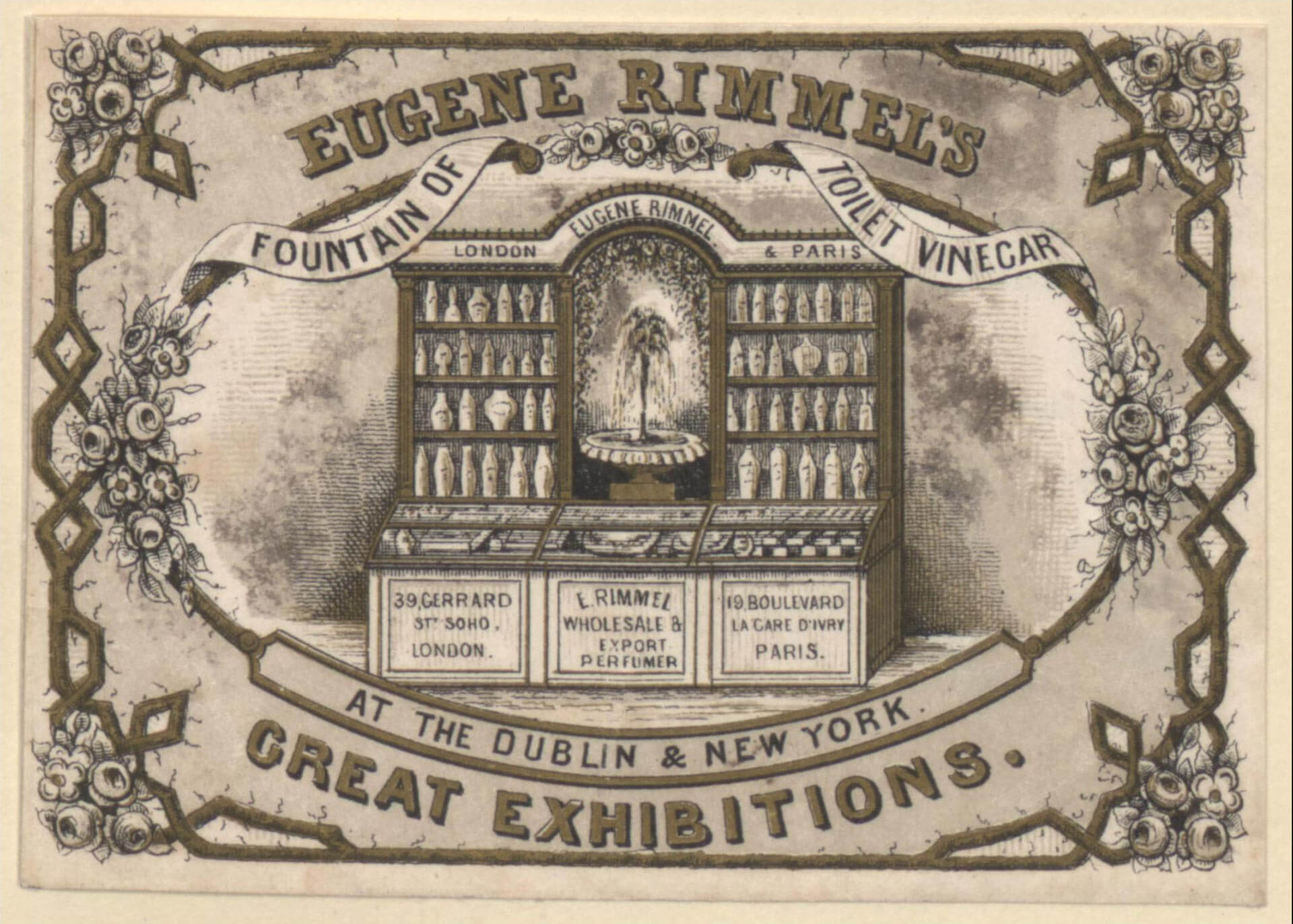

While these developments were happening, the deskilling of the craftsman and manufacturing of mass-produced items, expansion of factories and even...

Before industrialization, things were made in small numbers, carrying the emotions and fingerprints of its creator as a result of...

In 1400s AD, after several years of focused experiments, Johannes Gutenberg made the system scalable and led the way for...

The history of graphic design begins with the cave paintings. The prehistoric humans were marking their daily lives or the...

Starting from a simple stone ax, throughout the history we created a man-made environment, to survive and control the world...